By: Jon Farrow

1 Feb, 2019

Recent research co-authored by Melvyn Goodale, co-director of the Azrieli Program in Brain, Mind & Consciousness, sheds light on the way the brain unconsciously processes visual information by studying an individual with affective blindsight.

Melina Canning is a 49-year old Scottish woman with cortical blindness. Her eyes, nerves, and most of her brain are perfectly functional, but a series of strokes two decades ago damaged the parts of her brain that deal with consciously understanding and interpreting vision. She can’t see shapes, colours or faces, although she can detect some visual movement.

Canning cannot tell when she is looking at a face. But if she is presented with images of faces and asked to guess the emotions being shown, she succeeds much better than random chance would predict. Somehow, she is seeing the emotional content without realizing it.

Canning’s affective blindsight is interesting and counter-intuitive, but neuroscientists like Goodale think it is more than just a curiosity. The condition provides a window to the more primitive parts of the brain that process emotion quickly and unconsciously.

In Canning’s case, the lack of conscious awareness seems key to her ability to succeed at this seemingly-impossible task. When asked to slow down and say how confident she was about her guesses, her answers were correct no more often than if she had simply flipped a coin.

These striking findings led Goodale and his colleagues Chris Striemer and Rob Whitwell to conclude that the incoming visual information bypasses the areas that deal with conscious vision of faces. Instead of going to the primary visual cortex, the emotional parts of the images are being processed in another structure deep in the brain, called the amygdala. And since Canning’s amygdala works normally, she is able to interpret emotion. Perhaps the act of introspection, of evaluating how sure she was about her guess, somehow forced the information to try to find the damaged parts of Canning’s brain, where it met a dead end.

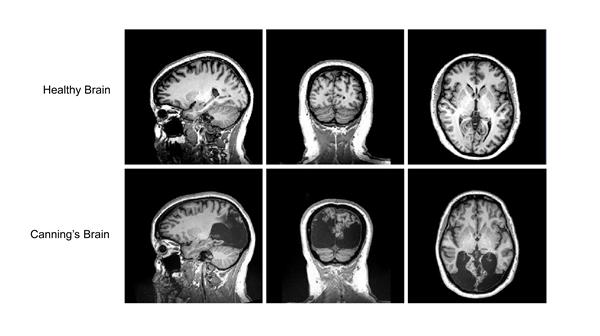

The damage in the visual areas at the back of Canning’s brain is extensive. Many of the cortical areas supporting visual face processing in her brain have been damaged by the strokes. The MRI of a healthy brain is shown for comparison.

“The processing is not in the cerebral cortex, but the signals are actually going to structures in the subcortex that we share with frogs and reptiles. These are very ancient pathways that are present in other animals,” says Goodale.

It may sound strange for visual information to bypass consciousness, but it happens all the time. According to Goodale, the eye sends information directly to more than 10 different targets in the brain, much of which goes completely unnoticed by our conscious selves. Our circadian rhythms, for example, get linked to the light and dark cycles of our surroundings without conscious awareness.

Canning’s condition is further evidence that emotional processing is accomplished at least partly unconsciously. The next puzzle is to figure out how this pathway to the amygdala works in normally functioning brains.

The research is published in Neuropsychologia.