By: Jon Farrow

4 Feb, 2019

A group of researchers recommend that the next set of Mars missions should be equipped with shovels and drills. Or at least subsurface radar.

The researchers argue that if there ever was life on Mars, it most likely retreated underground long ago. In a paper in Nature Astronomy they make a series of recommendations about how future Mars missions should search for it.

Missions to Mars have so far only scratched the surface, with the robotic rovers only breaching the first few centimetres of soil. The paper recommends using subsurface imaging and drilling techniques to explore from metres to several kilometres below the surface and focusing on fractured terrains where the products of underground processes may extend closer to the surface.

“Questions, in particular about whether there ever was or is still life on Mars, how the Martian climate changed over long periods of time, whether there still is liquid water and whether there are enough accessible resources for an extended human presence, will remain unanswered until we start to ‘go deeper’,” write the authors.

Although the surface of Mars is today believed to be a lifeless desert, it was once warm and wet. “There was standing water for sure. Whether that was in lakes and playas or an entire ocean is still up for debate”, says Barbara Sherwood Lollar, a professor of geology at the University of Toronto and co-author of the paper.

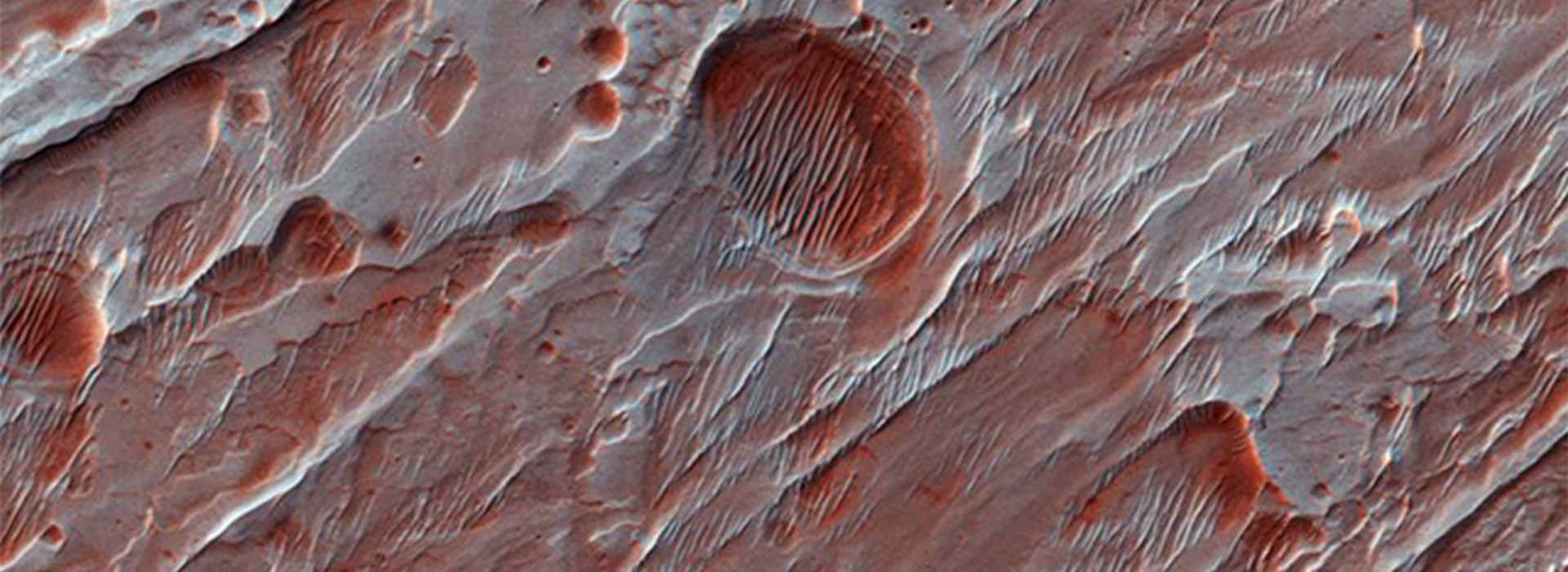

Mars has captured the imagination of scientists for centuries. The next discoveries lie under its surface. (Banner photo © NASA)

As the planet dried, liquid water retreated from the surface underground, where it remains today. If life depends on water, which is the current consensus, that means major discoveries about the possible history of life on the planet are waiting beneath the soil.

Jack Mustard, a co-author on the paper and professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences at Brown University, is enthusiastic about this frontier.

“The surface of Mars has been pretty inhospitable for a billion years. It’s not a place where any organism would survive for very long, nor would its byproducts be preserved,” he says. This is why he and his co-authors believe mission planners should start thinking about the subsurface now.

Questions, in particular about whether there ever was or is still life on Mars, how the Martian climate changed over long periods of time, whether there still is liquid water and whether there are enough accessible resources for an extended human presence, will remain unanswered until we start to ‘go deeper’.

But accessing information below the Martian surface won’t be as straightforward as strapping a jackhammer to the next rover.

“Trying to sort out how to get at the subsurface is hard. Because you can’t necessarily drill,” admits Mustard. The paper’s authors suggest a range of techniques that have worked well to expand our understanding of Earth’s subsurface. This includes polar ice cores, orbital monitoring, radar sounding and transient electromagnetics. These technologies could tell us about the composition and history of water on Mars, as well as make future colonization easier by telling us where to dig for resources.

The authors say we should turn our focus to the Martian subsurface not just because it’s uncharted territory, but also because there’s good reason to think we’ll find answers to long-standing questions if we dig.

Mustard and Sherwood Lollar are the leaders of a proposal in the CIFAR Global Call for Ideas: Earth 4D – Subsurface Science & Exploration. Many of the collaborators for this paper came together as a result of CIFAR workshops developing the proposal in the spring and summer of 2018.

The paper was published in Nature Astronomy on 14 January 2019.