By: Cynthia Macdonald

19 Jul, 2018

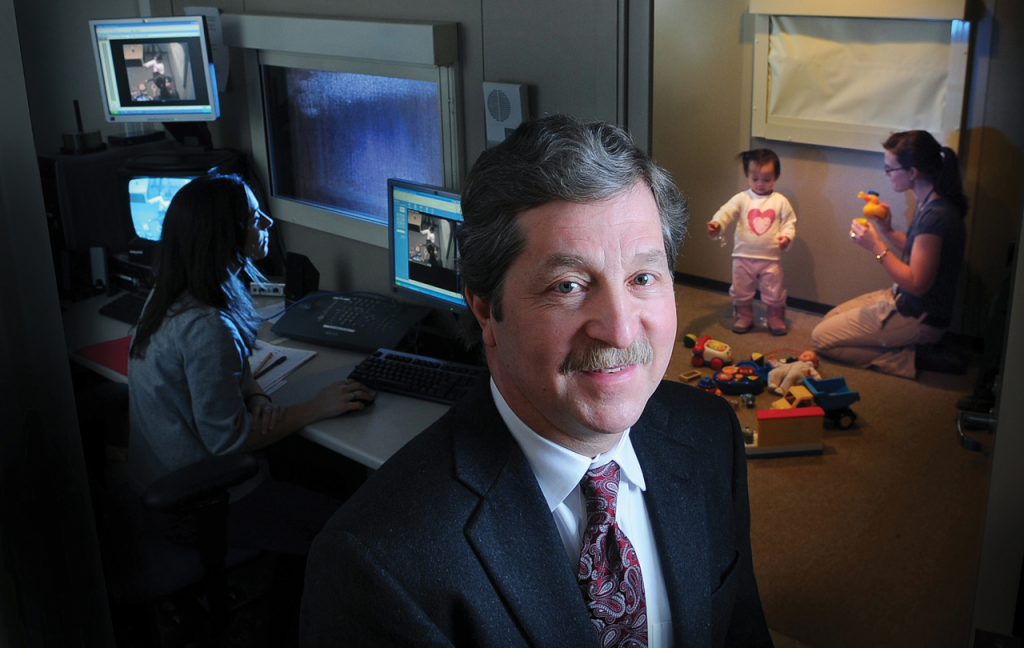

Charles Nelson studies what happens to children under the worst of conditions, from refugees in Dhaka to orphans in Romania. And while the results of abuse and neglect on the developing brain are grim, the lessons Nelson is learning provide hope that these children can be helped.

Dhaka doesn’t just have one slum area — it has thousands of them. With 500,000 people moving from rural Bangladesh to its capital each year, the city is said to be growing faster than any other on Earth. Services and infrastructure have been stretched well beyond the breaking point. Before they are even born, the children of Dhaka must contend with the brute reality of its poverty.

“This is a place where there are dirt roads, a very high density of people, tremendous pollution, open sewers,” says developmental neuroscientist Charles Nelson. “Because of unclean water and poor sanitation, the kids have chronic diarrhea. And on the psychosocial side, they live with high levels of domestic violence and maltreatment.”

Nelson is a senior fellow in CIFAR’s Child & Brain Development program, professor of pediatrics at Harvard, and head of the Laboratories of Cognitive Neuroscience at Boston Children’s Hospital. Using sophisticated imaging techniques, he has spent much of his career studying the ways in which severe adversity affects the developing brains of young children. And in Dhaka, the forms of adversity are apparently endless. “A goal of our project is to understand how they work individually and in aggregate, to impact the course of it all,” he says from his office in Boston.

On a dusty Dhaka street, Nelson’s research team has managed to install a neuroimaging lab in a small apartment building that also houses a medical clinic. This is no small feat, considering that four months before the lab opened, the building had no grounded electricity and a gaping construction hole in front of it. But with strong local partnerships and funds from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, it’s been up and running for over three years.

During that time, Nelson has been following a double cohort of children who were first screened at the ages of six months and three years, respectively. Initial test results — using MRI, EEG and a newer technique known as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) — have shown the three-year-olds to be “way behind” on cognitive development, with reduced metabolic activity (inferred from fNIRS) and altered connectivity (inferred from EEG). The study is intended to be longitudinal; it will follow the same children over several years, so it will be some time before Nelson can say definitively which insults, among the many faced by his Dhaka cohort, are worse than others.

He has some ideas, however. “We think that psychosocial features, such as violence in the house, may exert bigger effects than growth stunting. Growth stunting usually results from malnutrition; everybody assumes it’s bad for the brain, and it certainly is. But we may be showing that psychosocial adversity is even worse.”

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 9.0px; font: 7.0px ‘Circular Std’}

Brain imaging has shown the tragic results of neglect in Romanian orphanages.

Dhaka is not the only place that Nelson has studied children living in the worst of conditions. Since 1999, a landmark study he has co-led in Romania, known as the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), has revealed much about how a child’s brain responds — in some cases, permanently — to his or her environment during the first years of life.

The tragic story of Romania’s orphanage system is now well-known. In the misguided belief that population growth would lead to economic riches, former leader Nicolae Ceauşescu effectively banned both abortion and contraception. The consequence of this thinking was that, from the 1960s until the repressive dictator was executed in 1989, hundreds of thousands of unwanted children were placed in a series of grim, poorly run orphanages.

One survivor referred to the orphanages as “slaughterhouses of souls”; when Nelson and his team first started working in them, they made a pact with each other not to cry in front of the children. Babies lay in unchanged diapers, staring at white ceilings all day and developing permanently crossed eyes in the process; small children were often totally withdrawn, or clung wildly to strangers.

Romania was a far different environment from Dhaka — with modern plumbing and sanitation, the European children were far less afflicted by enteric disease. But without the benefit of the kind of familial attention seen in Dhaka, they’ve suffered profoundly from the trauma of extreme neglect.

“The kids in Dhaka are being clobbered with experiences that are not healthy for brain development,” Nelson says. “Whereas the kids in Romania were just not getting experiences. And it juxtaposes the differences. How does the brain wire itself if it doesn’t get a set of instructions? And how does it wire itself if the instructions it gets are less than optimal?”

The MRIs administered to children in Romania clearly showed that eight-year-olds had marked deficits in both grey matter (governing, among many other things, intelligence and emotional regulation) and white matter (the brain’s information highway, responsible for transmitting its thoughts and impulses). “In the Romanian orphanages, we found that the entire brain was affected,” Nelson says. “We believe these children may have fewer brain cells, or fewer connections.”

p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px 0.0px; line-height: 9.0px; font: 7.0px ‘Circular Std’}

“How does the brain wire itself if it doesn’t get a set of instructions?” Nelson asks.

Children thrive on loving attention, good nutrition and a safe environment, and the absence of any one of these is likely to be dangerous in some way. But Nelson’s work has revealed that early deprivation does not simply make children unhappy: because it interrupts their brain development, it may damage them beyond repair. The harsh truth is that without proper intervention, such damage can make leaving the grinding cycle of poverty all the more difficult.

To prevent this, timing is critical. Nelson has been able to show that when intervention occurs early enough, some pernicious effects can be reversed. Half of the 136 children in the Romanian study were placed in foster care, while the rest stayed in institutions. But when children were placed in a foster care environment before age two, their IQ and social functioning improved to a degree Nelson calls “overwhelming.” Children placed later improved, too, though not nearly as much.

In Dhaka however, “we can’t really examine critical periods very well, because we’re not manipulating anything,” Nelson says. “We just see delays and deficits. But the fact that we’re not seeing too much at six months — and a lot at 36 months — makes me wonder if kids need to be in these bad environments for a while before the brain goes off track.”

He has also noticed that functions such as cognition appear more amenable to recovery than other abilities, such as the goal-setting and self-control mechanisms known as executive functions.

Megan Gunnar is a psychologist and associate fellow in CIFAR’s Child & Brain Development (CBD) program whose research has also centred on early adversity in children, with an emphasis on those adopted from orphanages. She’s seen similar results in North America. While many of the children she has studied do succeed in life, especially those with resourceful parents, “they often struggle with attention problems,” says Gunnar. “The prefrontal cortex is very sensitive to early experiences, and we see disturbances in the development of the circuitry that supports executive function. We see this in imaging, and in the kind of tasks they’re able to do.”

Essential brain functions don’t come on all at once. Though the stage for poor outcomes may be set early in life, the results of adversity are only revealed in the fullness of time. This argues for the necessity of studying children, as Nelson does, in a longitudinal fashion.

In infancy, researchers can tell whether vision, hearing and motor skills are developing properly. But it’s only when children enter school that the abilities to read, write and get along with peers become measurable. In adolescence, other deficits may emerge, such as those related to executive functioning and intimate partner relationships. Among the Romanian orphans, psychosis and paranoia have just started to appear in teens who’ve been institutionalized their whole lives.

“One concern we’ve already had is that of those 136 kids who started life in an institution, 68 are girls. And of those, nine of them had had babies by the time they were 15,” says Nelson. “So we’d like to follow that up.”

The children of Dhaka deal with a multitude of threats, including pollution, malnutrition and microbial illness.

Naturally, many ethical questions surround the study of children living in squalor. The BEIP was a randomized control trial; as with others of this type, half the subjects received treatment and half didn’t. Unlike other such trials, though, it was likely from the outset that children removed from orphanage care would fare better than those left in it. Wouldn’t it have been preferable to just close the orphanages, and place every single child with a caring foster family?

Unfortunately, that option wasn’t available in Romania in the early 2000s. The country did not have a foster care system, and most of the parentless children were not, in fact, literal orphans: without proper resources to raise them, their parents had simply abandoned them in orphanages.

Still, after a lengthy interview process and the cooperation of local NGOs, Nelson’s team managed to find, train and fund enough competent adults to foster about half of his cohort. When the initial research period was over, they staged a press conference in Bucharest to draw attention to the radical differences between orphanage and home care. They then called on the government to pay for foster parenting.

That system is now in place. While institutional care hasn’t been fully eradicated in Romania, it is forbidden for children under the age of two (except in cases of severe disability).

Nelson admits that fixing the situation in Dhaka will be far more difficult. With a current population of 18 million, its numbers swell every day with the presence of “climate refugees” driven toward the city from a receding coastline. Many of these live in the slums.

“But there are concrete steps we can take,” Nelson insists. “We can intervene in domestic violence, and in child maltreatment. We can clean up the water, we can improve the vaccination rate, we can cure their enteric disease.”

Any one of these problems could prove harmful to the developing brain. The widespread presence of potentially harmful gut pathogens in Dhaka is a relatively recent concern for neuroscientists, given new research on the relationship between microbiota and the brain. But Nelson wants to use a combination of therapy and imaging technology to identify the most pressing needs first, so that interventions can be precision-targeted.

“I don’t think we ever expected a simple answer,” says behavioural geneticist Marla Sokolowski, co-director of CIFAR’s CBD program. “Now, at least, scientists know what many of the problems are. Physical abuse used to be the only thing that was thought to affect children in a very negative way. But now we know that the slow drip of neglect, even without physical abuse, can be just as bad. Because adversity is so multidimensional, we need to bring together people from all kinds of disciplines. Chuck brings expertise in psychology, as well as in neuroscience.”

On occasion, those brain images are surprising. Even with everything against them, a minority of children are able to survive, thrive and lead relatively normal lives. “Some kids are exposed to horrible experiences, but don’t show any developmental sequelae because of them,” Nelson says. “In Romania we tried to identify key protective factors, but there’s still this issue of individual differences — a combination of genetics and other things that we don’t yet fully understand. So we expect there will be some kids in Dhaka who look unfazed by these experiences. And others who will be profoundly impacted. And the big question for us is, which is which, and why is that?”

He’s also availed himself of new techniques. Scanning babies in an MRI machine might once have seemed impossible, given the punishing din of this particular test on adults, but the team has developed a technique to test infants who are fully asleep, clad in special “swaddle sacks.”

We can intervene in domestic violence, and in child maltreatment. We can clean up the water, we can improve the vaccination rate, we can cure their enteric disease.

But while MRI reveals a lot about the brain’s structure, other technology is needed to measure how it’s actually functioning. For this, scientists have traditionally relied on functional MRI scanning (fMRI). But fMRI tests aren’t easy on children, in that they require them to sit still for long periods of time. Instead, Nelson uses fNIRS, which is shorter and more readily accommodates a fidgety patient. He also uses EEG, which measures electrical activity in the brain.

And the people of Dhaka are involved not only as test subjects, but as data collectors, too. “We have a staff of about maybe 15 local people,” Nelson says. “They operate the lab there. Some of them are the physicians who see these kids, and have gotten to know them really well. The other thing is that we’ve brought them here to Harvard a couple of times for training. So even long after our study is over, they’ll have the intellectual capital there to continue this work on their own.”

Nelson’s studies are well-known to psychologists working with children in impoverished societies around the world, in places far removed from the relative comfort of North America. Are these issues relevant to our own society?

“I think they are,” says Sokolowski. “I mean, if you look at the Indigenous population on reserves — I don’t have to say any more. This is happening in Canada. And even in wealthy populations there’s abuse and neglect that isn’t spoken about. This is not, about ‘them and us.’ It’s about all of us.”

Nelson’s career is unique in that it has involved three distinct domains: developmental psychology, neuroscience and humanitarianism. Emotionally, it has been extremely draining. But it’s also had a directly positive effect on the lives of many, and promises to do so for years to come. Thanks to Nelson’s work, we can be sure that while nature is a powerful determinant in brain development, nurture plays a large part, too. He has ensured that children’s brains can be studied both ethically and effectively. He is ferreting out the greatest dangers to a vulnerable cerebrum. And, perhaps above all, he is making direct interventions that save lives.

“Chuck is a fantastic researcher and he’ll go anywhere in the world to find the answers to questions that he’s asking,” says Sokolowski. “Everyone wants the best for their children, no matter what their circumstances. They’re happy that someone is thinking and caring about them, so that they can have better lives. Heroic — that’s the word for what he does.”

We depend on you to help create impact like this.