By: Jon Farrow

30 May, 2019

When a zebrafish is mature, its horizontal bands of dark and light scales bring to mind its namesake on the savannah. Not an ugly fish, but not remarkable either.

In its larval stage, however, it’s another story. For about three days after they emerge from their eggs, zebrafish are completely transparent. This makes them beautiful to biologists such as Karen Guillemin, a fellow in CIFAR’s Humans & the Microbiome program, and her post-doctoral fellow Travis Wiles, because the inner processes of the fish can be captured with a microscope.

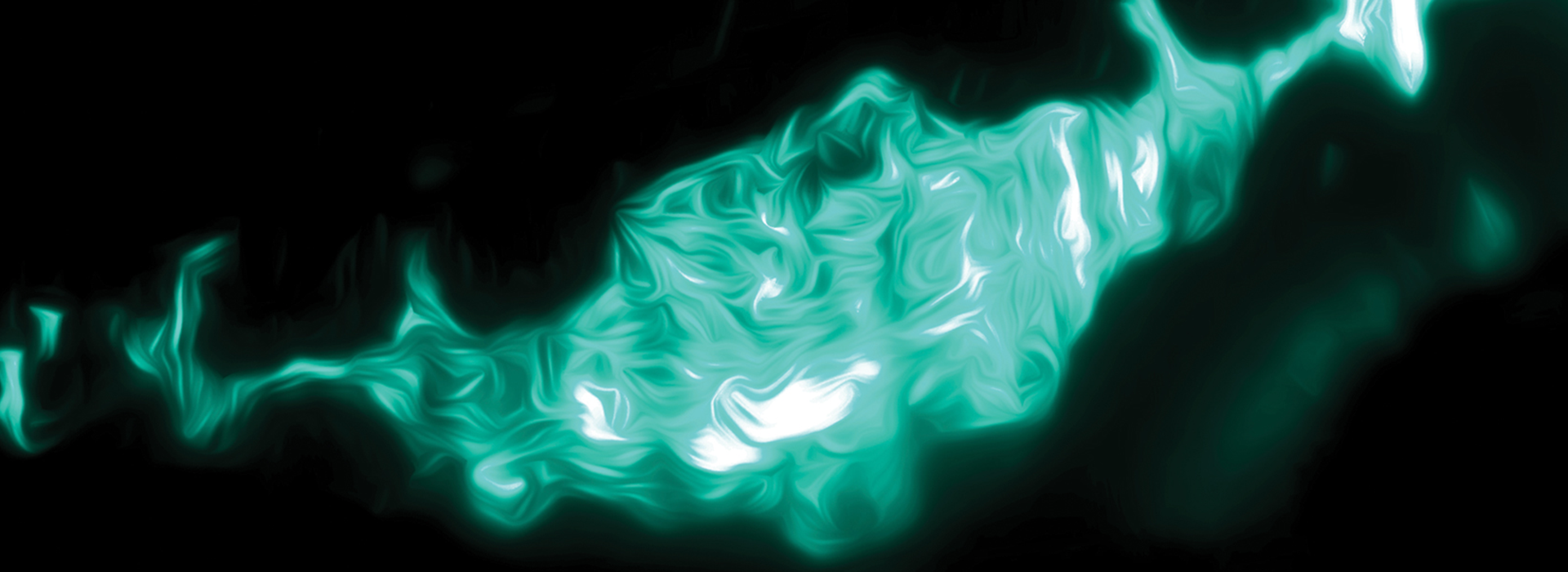

The bright, swirling patterns shown here might bring to mind deep water caves, the aurora borealis or mysterious astrophysical phenomena. But the truth is much smaller: this is a long-exposure photograph, taken over a few seconds, of fluorescent Vibrio bacteria moving in the intestine of a larval zebrafish. At actual size, the pictured area would fit on the head of a pin.

The bacteria swim and bustle at quite a clip, some reaching speeds of a tenth of a millimetre per second. “If you scale that up based on body length to human scale, that would be like the average-sized person running 600 kilometres an hour,” Wiles says.

Understanding the dynamics of how bacteria live and move inside another creature can have big implications for health and well-being. CIFAR’s Humans & the Microbiome program is exploring just that. Their work seeks to explain how microbes that live in and on us affect our health, development and even behaviour.