By: Liz Do

30 Jun, 2022

John Mustard’s academic journey to Mars began under the sea.

Mustard, co-director of CIFAR’s Earth 4D: Subsurface Science & Exploration program, initially wanted to be like famed oceanographer, Jacques Cousteau.

“I was going to be a marine biologist. I quickly realized that that wasn’t the path for me,” he explained. Trained as a traditional geologist and looking for what to pursue after graduation, an ad for a planetary science graduate program caught his eye. And he never looked back.

Thirty years later, Mustard is a professor at Brown University, studying the crustal composition and the role of water on Mars and the Earth’s Moon. Involved in the exploration of Mars since 1989, Mustard seeks to answer seemingly impossible questions, such as: are we alone?

In a Q&A with CIFAR, Mustard shares insights on his current projects and the exciting future of Mars exploration.

CIFAR: What’s something you’ve overcome in your research that once seemed impossible?

John Mustard: Barbara Sherwood Lollar, co-director of Earth 4D, and I got very strongly connected over a presentation I saw her give. She discussed research published on the potential of Greenstone belts in Canada, where a lot of mining happens, to generate hydrogen. She showed these ancient green-coloured rocks produced enough hydrogen underground to sustain lots of underground biology — ecosystems underground equivalent to the Earth’s seafloor.

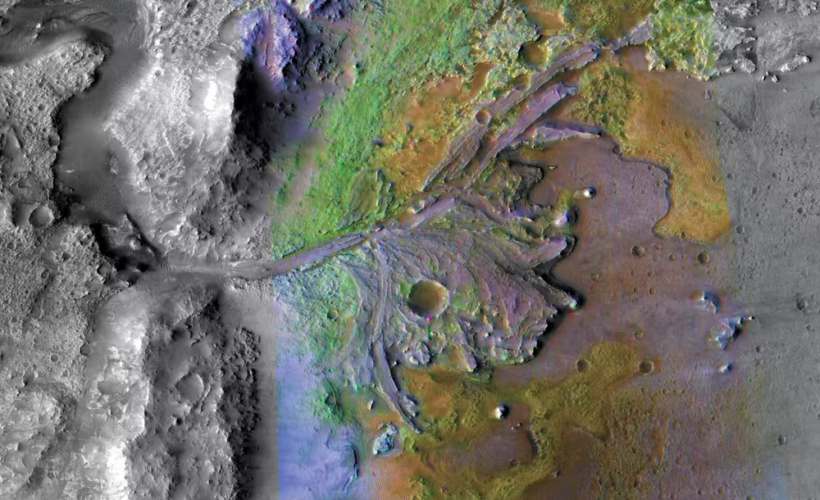

I looked at that and I said, that is remarkable because those are the same rocks that exist on Mars. That means that the potential for Mars to generate enough hydrogen to sustain an entire underground ecosystem is definitely in the cards. We started building it up from there and six years later, we have a number of papers about it.

We know life on Mars is really a tough go. The surface of Mars is toxic from the radiation environment, the atmospheric pressure is one one-hundredth of Earth’s pressure, there’s no water, it’s cold, it never gets warm. So to imagine that life ever got started on the surface of Mars, where everyone lived happily, seems to be such a distant concept. But the fact that it has the right ingredients to produce a happy subsurface ecosystem was just a major moment.

CIFAR: What projects are you working on right now?

John Mustard: There are these absorption bands in the spectrum surface of the Moon that we know are due to water. Water on the Moon! What a concept. But there are no spacecraft instruments that cover that wavelength region with the fundamental absorption band.

I’m working with my former graduate student and we’re designing a science instrument that could go on a spacecraft to detect water [in these absorption bands]. It’s a long process and we’re currently putting together the specifications. Then we’ll work with the Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, California — one of NASA’s centres for robotic space exploration. It will take a few years but that’s going to be really fun.

Another project that’s front and centre in my mind is one through CIFAR. I’m working closely with my Earth 4D peers to map out a three-dimensional architecture of planets. It all comes back to understanding the interior. If we can understand this three-dimensional architecture, we can then figure out what underground organisms lived happily as they generated the hydrogen needed within their Greenstone belt.

CIFAR: Looking ahead at the next decade or so, what are some things that excite you about the potential of your work?

John Mustard: Well, the compact spectrometer we’re talking about, could really revolutionize our understanding of the composition of the Moon, and surprisingly, Mercury.

CIFAR: How so?

John Mustard: This has the potential to revolutionize how we study the Moon because it will allow, for the first time, the capability to detect and quantify iron and magnesium contents of rock-forming minerals that are critical to unraveling competing theories on the Lunar origin and evolution. And for Mercury, it would allow detection of minerals that to this day have been invisible to the existing suite of remote-sensing instruments.

CIFAR: And what excites you about the future of your field?

John Mustard: The Moon is going to be a busy site of exploration over the next 10 years. There’s a lot of international interest there, with six nations (Japan, South Korea, Russia, India, the United Arab Emirates and the United States) having their sights on sending something to the Moon. NASA is going to send the first humans back to the Moon. In that same timeframe, they’re going to need tools and instruments — we think our instruments could be a component that they would want to bring with them.

CIFAR: Is establishing a settlement on Mars as science fiction-sounding as it seems?

John Mustard: There are days when I think it’s inevitable, because the push and the drive is like nothing I’ve ever experienced in my career. Under a commercial drive, there is some possibility.

I’ve been to the SpaceX rocket plant and talked to some of their people about what they’re planning on. And I know they’re pretty serious. Another company, Blue Origin, is probably not far behind. This is unleashing the creativity of the engineers to achieve something remarkable.

I teach a course called Mars, Moon, and the Earth. One of the things we talk about is whether it’s right to commercialize space. William Shatner went into space when I last taught the course and we watched that in class. Shatner comes out of the capsule, and he’s just speechless. But then he was able to articulate some of what he was feeling and some of what he saw. And that was just one of the most engaging communications from someone who had just been to space that I had ever seen. Because it comes from an actor – someone who’s kind of closer to what you and I are – rather than an astronaut, it just struck me as an amazing example of where we are. I have no doubt that this commercialization is going to pick up speed. But I think it’d be a long time before we see human missions to Mars. We’ll need the technology for a sustained presence, whether it is the Moon or Mars.

CIFAR: As we celebrate 40 years at CIFAR, you have a unique and familial connection to this organization’s origins. Your father was the founding President. How has the organization played a role in your research career? What do you want people to know about CIFAR?

John Mustard: I have five siblings, so growing up you know there’s going to be a lively table at times. And when my dad would talk about his day — wow — he would pick up on all of these ideas that were coming out of CIFAR at the time. He was super excited about it. He would talk about robotics, for example, which is very far away from his research on platelets (Fraser researched heart disease and early childhood development). But you could see how it just totally energized and charged him up.

CIFAR is about this unrestricted embracing of ideas, and setting the table so that remarkable things can happen. That isn’t possible without the incredible effort on the part of the people at CIFAR and its leadership. I certainly knew from my dad’s experience what CIFAR leadership do to keep the ship running, to tackle those important funding questions, in order for us to tackle our science questions.

As part of CIFAR’s 40th anniversary celebration, “Believe the Impossible: The Future of…” highlights researchers whose big ideas could transform their field over the next 40 years.