By: Bob Holmes

17 Jun, 2016

Three years later, icebound in the Canadian high Arctic and unable to figure out how to keep warm or feed themselves, the remnants of Franklin’s expedition starved to death. They died in an environment the Inuit had occupied comfortably for generations – so comfortably, in fact, that a nearby bay was known locally as Uqsuqtuuq (“lots of fat”).

Franklin’s men were mostly young and healthy, well-equipped with the latest European technology, and had no children or old people to support. Yet over their three-year ordeal they failed to learn how to survive. Why?

The answer, according to Joseph Henrich, is that they lacked something the Inuit possessed: a package of adaptations for Arctic living that evolved culturally over thousands of years. The Inuit knew how to hunt seals, find fresh water, make snow houses, heat them with seal-oil lamps and perform a thousand other skilled tasks far too complex to work out in a single lifetime.

The story of the Franklin expedition illuminates a key fact about humans and our success as a species. We survive and thrive not because of our individual adaptability and intelligence, which are rather over-rated. Instead, cumulative cultural evolution is what makes us so successful as a species, and is the key to understanding how evolution has shaped our anatomy, physiology and psychology over the last few million years.

“Our species’ immense ability to adapt to diverse environments and develop large bodies of know-how is due to our unique ability to learn from others, not to our raw brainpower,” says Henrich, who is a senior fellow in CIFAR’s Institutions, Organizations & Growth program and holds appointments in Harvard University’s Department of Human Evolutionary Biology and at the University of British Columbia.

“Our intelligence alone isn’t the whole story, or the most important part of the story,” he says. “We need the cultural knowledge.” Henrich develops these ideas further in a new book, The Secret of Our Success, published in 2015.

Captain Sir John Franklin, left, perished with 128 offi cers and crew after they became trapped in the ice off of King William Island.

Henrich likes to point out that of all the mental skills, social learning is the one where humans excel most compared with other species. Researchers have recently shown that chimpanzees and orangutans do almost as well as human toddlers in tests of spatial reasoning, tool use, understanding causality and estimating quantities. In other studies, chimps compare well – even with adult humans – in tests of working memory, information-processing speed and simple strategic-game reasoning. But when it comes to watching and imitating others – social learning, in other words – we humans leave our simian cousins in the dust.

We’re not the only species to practice social learning, of course. Chimps do learn from one another, too, as do a few other species, such as orcas. But at some point in our evolutionary past, ancestral humans got so good at social learning that cultural knowledge began to accumulate from one generation to the next, so that the whole process began to snowball.

This changed the evolutionary game. Suddenly, the ability to acquire this expanding body of cultural knowledge became the most important skill of all. Any adaptations that improved cultural learning – such as an innate tendency to imitate others – were therefore favoured by evolution. This, in turn, helped cultural knowledge accumulate more quickly, making this kind of learning even more valuable – a self-reinforcing cycle.

One way to learn more effectively is to imitate the right people. If you want to learn to hunt, tag along with a successful hunter. If you want to learn to cook, help a skilled cook. Skilled and successful models have what is called ‘prestige’ – a new form of status, almost unique to humans, that is based on knowledge and ability rather than raw physical power. Humans have evolved to instinctively imitate prestigious individuals. (This explains why car companies and insurance companies pay famous athletes millions of dollars to endorse their products – we tend to copy what they do, even outside their field of expertise.)

As cultural evolution progressed, our ancestors’ environment became more and more defined by cultural adaptations such as fire and tools. This, in turn, began to shape the physical adaptations of our species. “That’s been a kind of duet, a kind of dance, with our genetic evolution for hundreds of thousands of years,” says Henrich. “What we are can only be understood by understanding the pressures that culture put on our genes.”

Consider our anatomy. Our jaws and teeth, for example, are much smaller and weaker than those of chimps and gorillas. Almost certainly, that’s because we have developed the package of cultural adaptations known as cooking, which makes food quicker and easier to chew. Look also at our efficient bipedal gait, hairless bodies and copious sweat glands. These are best understood as adaptations for pursuing prey animals to exhaustion in warm climates, a technique that some hunter-gatherers still use today. But this hunting strategy works only if the hunters have the cultural knowledge to track individual animals for long distances, and to find or carry water during the long pursuit – a clear case of cultural adaptations feeding back to affect physical traits.

Over time, cultural practices that help people survive gain widespread adoption, even when the reasons for them might not be obvious. In Fiji, for example, where Henrich has done fieldwork, taboos prevent pregnant and breastfeeding women from eating certain types of reef fish. None of the women know why – it’s just taboo. But Henrich and his wife Natalie later found that the taboo covered precisely the fish species most likely to carry ciguatera toxin, which is apt to harm fetuses and infants.

Similarly, cultures in the Amazon process manioc root, a staple food, through an intricate, multi-step process that involves scraping, grating, soaking and boiling the roots, then letting them stand for two days before eating. All of this is crucial because it prevents poisoning from high levels of cyanide in the unprocessed roots. To the people themselves, though, it’s merely what they’ve always done. Few have ever seen cyanide poisoning, because no one deviates from the cultural practice. In effect, says Henrich, the culture itself is smarter than the people in it.

The same is true, of course, of our own culture and its practices. Take our strong preference for monogamous marriage, for example. Most of us accept the norm, but few can explain why, other than to say, “That’s the way it is.” Actually, there’s more to it. “When you analyze normative monogamy, you find out it’s doing some functional work,” says Henrich. Mono-gamy fosters social harmony by providing most adults of both sexes with a mate, and this may have helped our set of social norms survive over many generations.

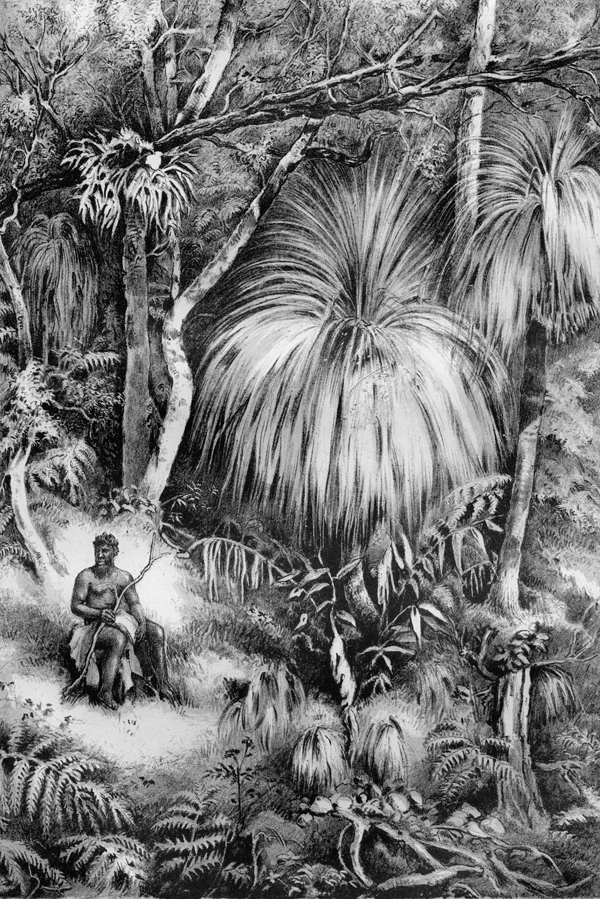

An 1879 depiction of a Tasmanian islanders. Tasmanians were cut off from the mainland they gradually lost learned skills including the ability to make fi re and fi tted clothes.

Cultural differences like these, evolved over time by particular cultures, are what attracted Henrich to this area of research in the first place. He originally trained as an aerospace engineer, but his interest in anthropology led him back to graduate school and to fieldwork among the Matsigenka tribe in the Peruvian Amazon. There, he was struck by how unwilling the Matsigenka were to work together for the common good in tasks such as cutting grass. He began to wonder if this reflected a different set of learned social norms. To test this idea, he asked them to play the ultimatum game, a favourite tool of economists.

In the game, one player is given a sum of money and told to divide it with a second player. If the second player accepts the division, each gets to keep their share; if the second player refuses, neither gets anything. Rationally, the second player should accept any offer, since even a small amount is better than nothing. But people from Western societies almost uniformly reject anything much less than a 50:50 split. This reflects our societal idea of fairness. In contrast, none of the Matsigenka ever rejected an offer, no matter how small. They had learned a different set of norms, and thus weren’t culturally primed to expect a fair split.

This got Henrich thinking. Back in North America, he took a year away from his graduate research to read not just about anthropology, but also economics, sociology, psychology and evolutionary biology.

“I was interdisciplinary from the beginning, because I wanted to explain the economic decision-making of these people in Peru,” he recalls. He even drew on his aerospace engineering training, which helped him understand the sophisticated mathematics of evolution with both genetic and cultural inheritance. He found a rich lode in the intersection of all these fields, and has now been developing his ideas for nearly two decades, often using economic games to compare social norms across societies.

Henrich’s work is a perfect fit for CIFAR’s program on Institutions, Organizations & Growth, which seeks to understand why some societies are more successful than others.

“People like Joe are really key to our work,” says Program Director Torsten Persson, an economist at Stockholm University. “A multi-faceted approach to understanding societies brings richness to the discussion.” In particular, Persson points to Henrich’s cross-social survey of economic games. “That’s a good example of how different contexts produce different behaviours. It makes all of us think about the importance of cultural context.”

In essence, Henrich’s position is that it’s better to be social than to be smart: the vast majority of our knowledge comes from other people, not from figuring things out on our own.

“We rely on a collective brain,” he says. “The larger and more connected a population, the more technologies it can produce.” Isolation leads to cultural and technological poverty, as illustrated dramatically by the Aboriginal Tasmanians. After rising sea levels isolated them from the mainland, they gradually lost the knowledge of bone tools, stone spear points, fishing, fitted clothing and almost every-thing else, ending up with the simplest tool kit known among modern humans.

Going much further back, it may have been isolation that did the Neanderthals in. Based on brain size, Neanderthals were probably slightly smarter than us, at least in raw processing power. But they lived in small, widely scattered groups in ice-age Europe. Henrich hypothesizes that they probably lacked the large collective brain that allowed our more social African ancestors to evolve better cultural packages.

Modern humans stayed connected, and their technologies and genes continued to co-evolve. That brings us to today, when we routinely connect more quickly to more people and ideas than our prehistoric ancestors could have imagined. And that’s a good thing, since it allows our collective brain to be exposed to more ideas, more ways of doing things. “If you buy the collective brain,” says Henrich, “then infusion of new ideas brings large benefits.”

And he says we’re probably not done changing yet. Our technology will continue to interact with our genes in ways we can’t necessarily predict. Cooking gave us easier access to the energy content in food, and reduced the size of our guts and teeth. It’s hard to tell what the advances in communications technologies will do to our brains and bodies, but it seems likely that the changes haven’t stopped.

“Genes and culture evolve together,” Henrich says. “Culture has always driven evolution. We should expect that to continue to happen.”